|

Home

Bibliography

Calendar

Columns

Dorothy Brizill

Bonnie Cain

Jim Dougherty

Gary Imhoff

Phil Mendelson

Mark David Richards

Sandra Seegars

DCPSWatch

DCWatch

Archives

Council Period 12

Council Period 13

Council Period 14

Election 1998

Election 2000

Election 2002

Elections

Election

2004

Election 2006

Government and People

ANC's

Anacostia Waterfront Corporation

Auditor

Boards and Com

BusRegRefCom

Campaign Finance

Chief Financial Officer

Chief Management Officer

City Council

Congress

Control Board

Corporation Counsel

Courts

DC2000

DC Agenda

Elections and Ethics

Fire Department

FOI Officers

Inspector General

Health

Housing and Community Dev.

Human Services

Legislation

Mayor's Office

Mental Health

Motor Vehicles

Neighborhood Action

National

Capital Revitalization Corp.

Planning and Econ. Dev.

Planning, Office of

Police Department

Property Management

Public Advocate

Public Libraries

Public Schools

Public Service Commission

Public Works

Regional Mobility Panel

Sports and Entertainment Com.

Taxi Commission

Telephone Directory

University of DC

Water and Sewer Administration

Youth Rehabilitation Services

Zoning Commission

Issues in DC Politics

Budget issues

DC Flag

DC General, PBC

Gun issues

Health issues

Housing initiatives

Mayor’s mansion

Public Benefit Corporation

Regional Mobility

Reservation 13

Tax Rev Comm

Term limits repeal

Voting rights, statehood

Williams’s Fundraising Scandals

Links

Organizations

Appleseed Center

Cardozo Shaw Neigh.Assoc.

Committee of 100

Fed of Citizens Assocs

League of Women Voters

Parents United

Shaw Coalition

Photos

Search

What Is DCWatch?

themail

archives

|

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL

SUMMARY OF SPECIAL REPORT: Emergency Response to the Assault on David E. Rosenbaum

CHARLES J. WILLOUGHBY

INSPECTOR GENERAL

OIG No. 06-I-003-UC-FB-FA-FX

June 2006

This Summary describes the D.C. Office of the Inspector

General’s review of the emergency response efforts provided by District agencies and hospital

personnel in light of applicable policies and procedures. The OIG is providing this Summary in

lieu of the full report in accordance with the exemptions provided in the District of

Columbia Freedom of Information Act (D.C. Code §§ 2-531-539 (Supp. 2004)) to preserve the

privacy interests of Mr. Rosenbaum and other individuals mentioned in the full report.

Table of Contents

Letter to the Mayor

Executive Summary

Background and Perspective

Scope and Methodology

Findings and Recommendations

Conclusion

Operations and Protocols of District Agencies and Howard

University Hospital

Office of Unified Communications

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department

Metropolitan Police Department

Howard University Hospital

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner

Chronology of Events

Discovery of “Man Down” and 911 Call for Assistance

Office of Unified Communications Response

Universal Call Taker

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Dispatch

Metropolitan Police Department Dispatch

Issue and Finding

Did the Office of Unified Communications properly handle,

dispatch, and monitor the incident?

Recommendation

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Engine 20 Response

Engine 20 Arrives at Gramercy Street

Firefighter Interviews

Residents’ Observations

Issues and Findings

Did FEMS employees follow all rules, policies, protocols,

and procedures?

Did first responders properly assess the patient?

Were written reports and oral communication

adequate?

Recommendations

Metropolitan Police Department Officers Response

MPD Units Arrive at Gramercy Street

MPD Officer Interviews

Initiation of Assault and Robbery Investigation

Issue and Findings

Did MPD responders properly assess the situation at the

scene, and were steps taken by MPD responders prior to opening an

investigation adequate?

Recommendations

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Ambulance 18 Response

Ambulance 18 Arrives at Gramercy Street

Emergency Medical Technician Interviews

Issues and Findings

Did Ambulance 18 EMTs follow all rules, policies,

protocols, and procedures?

Did Ambulance 18 EMTs arrive with all due

and proper haste?

Did Ambulance 18 EMTs properly assess the patient?

Did Ambulance 18 EMTs select an appropriate hospital?

Were written reports and oral communication

adequate?

Are there any identifiable improvements to FEMS rules,

policies, protocols, and procedures?

Recommendations

Howard University

Hospital Emergency Department Personnel Response

Ambulance 18 Arrives at Howard University Hospital

Hospital Personnel Interviews

Issue and Findings

Did Howard University Hospital properly triage and assess

the patient upon his arrival at the hospital?

Recommendations

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner Response

Autopsy of David E. Rosenbaum

Issue and Findings

Did the OCME promptly and completely discharge

its review and report of the death?

Recommendation

Conclusion

Appendices

Appendix 1: Interviewees’ Contradictory Statements

Appendix 2: Map, Ambulance 18 Route to Gramercy Street

Appendix 3: FEMS Form 151 Run Sheet (not available online)

Appendix 4: Map, Ambulance 18 Route to Howard University

Hospital

Appendix 5: Ambulance 18 Log Sheet Entry (not

available online)

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Office of the Inspector General

717 14th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005 (202)

727-2540

Inspector General

June 15, 2006

The Honorable Anthony A. Williams

Mayor

Office of the Mayor for the District of Columbia

1350

Pennsylvania Ave. N.W., Suite 600

Washington, D.C. 20004

Dear Mayor Williams:

In response to Mr. Bobb’s request that the Office of

the Inspector General (OIG) review the response to the January 6, 2006,

incident involving David E. Rosenbaum, please find enclosed our final

report. My Office reviewed the actions of the Office of Unified

Communications (OUC), the Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department

(FEMS), the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), Howard University

Hospital, and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME), regarding

their response to the incident.

In order to conduct this review, I appointed a team of

investigators and inspectors who have training and experience in law

enforcement, firefighting, medical care, and prehospital care. The team

reviewed policies, procedures, protocols, General and Special Orders,

personnel files, patient care standards, hospital and ambulance medical

records, certification and training records, and reports issued by FEMS,

MPD, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, and the Department of

Health. The team also interviewed all District government and Howard

University Hospital personnel involved in Mr. Rosenbaum’s emergency

care and the autopsy.

The OIG team concluded that, with the exception of OUC

and OCME, there was an unacceptable chain of failure in the provision of

emergency medical and other services to Mr. Rosenbaum as required by

FEMS, MPD, and Howard University Hospital protocols. Individuals who

played critical roles in providing these services failed to adhere to

applicable policies, procedures, and other guidance from their

respective employers.

These multiple individual failures during the Rosenbaum

emergency suggest alarming levels of complacency and indifference which,

if systemic, could undermine the effective, efficient, and high quality

delivery of emergency services to District residents and visitors. Our

review indicates a need for increased oversight and enhanced internal

controls by FEMS, MPD, and Howard University Hospital managers in the

areas of training and certifications, performance management, and oral

and written communications, as well as employee knowledge of protocols,

General Orders, and patient care standards. The OIG recommends, among

other things, that FEMS and MPD implement quality assurance programs

that would assign quality assurance responsibilities to the best-trained

or most senior employees dispatched to every medical and non-medical

emergency.

In order to give your office and the affected District

agency heads the clearest and most useful picture of the actions we

reviewed, this full version of the report contains the names of the

individuals involved, medical information, and sensitive personnel

information that should be handled securely. In addition, we are

enclosing a redacted version of the report without names and other

sensitive information, which will be available to the public on the OIG

website.

The significant concerns resulting from this review will

necessitate follow-up to our recommendations by the affected District

agency managers. So that I can be assured that our findings and

recommendations have been given the attention warranted, I request that

corrective actions that you require and receive from the agencies be

provided to me as soon as possible.

If you have questions about this report or if we can be

of further assistance, please feel free to contact me on (202) 727-9501.

Sincerely,

Charles J. Willoughby

Inspector General

CJW/ld

“Man Down.” On January 6, 2006, at approximately 9:20

p.m., a resident of Gramercy Street, N.W. went to his car to retrieve an

item and found an unknown man lying on the sidewalk in front of his

home. The resident’s wife called 911, and the Office of Unified

Communications dispatched emergency responders to the scene for a “man

down.” The fire (first responders), police, and ambulance (second

responders) personnel who were at the scene did not detect serious

injuries, illness, or evidence that the then-unknown man had been

physically attacked. He had no identification in his pockets, but was

wearing a wedding band and a watch. Stereo headphones were found near

him on the grass. Because he was vomiting, and because one or more

responders thought they smelled alcohol, the man was presumed to be

intoxicated. Consequently, the man was classified as a low priority

patient and transported to the Howard University Hospital (Howard)

Emergency Department where, after lying in a hallway for more than an

hour, medical personnel discovered that he had a critical head injury.

At approximately 11:31 p.m., Rosenbaum’s wife reported

to the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) that her husband, David E.

Rosenbaum, had gone for an after-dinner walk at approximately 9 p.m.,

but had not returned. The police broadcast a descriptive lookout, and a

police officer who had responded to the Gramercy Street “man down”

call realized that the description of the missing person matched that of

the man who had been found lying on the sidewalk. It was later

determined that the “man down” was David Rosenbaum.

Mr. Rosenbaum’s head injury was discovered at Howard in

the early morning hours of January 7 and reported to MPD. MPD officers

then returned to the Gramercy Street scene to look for evidence that

might indicate the cause of the head injury. Later, on January 7, the

Rosenbaum family was alerted by credit card companies to unusual

activity on Mr. Rosenbaum’s credit cards. MPD subsequently linked Mr.

Rosenbaum’s injuries, his missing wallet, and the unusual credit card

activity, and initiated an assault and robbery investigation.

Despite surgery and other medical interventions to save

him, Mr. Rosenbaum died on January 8, 2006. The autopsy report issued on

January 13, 2006, by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner concluded

that Mr. Rosenbaum was a victim of homicide due to injuries sustained to

his head and body.

Following Mr. Rosenbaum’s death, numerous questions

were raised and complaints made by both citizens and District government

officials about the emergency medical services provided to him by D.C.

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department (FEMS) and Howard

personnel. Questions were also raised regarding the delayed recognition

by MPD officers that a crime had been committed.

In a letter to the Inspector General dated January 19,

2006, City Administrator Robert C. Bobb requested that the Office of the

Inspector General conduct a review of the response to David E. Rosenbaum’s assault and subsequent

death.1 Mr.

Bobb indicated that he and Mayor Anthony A. Williams wanted the review

“to ensure the maintenance of public confidence in the emergency

services provided by the District government.” In his letter to the

Inspector General, Mr. Bobb asked that the Office of the Inspector

General’s review specifically include answers to the following

questions:

- Did the Office of Unified

Communications properly handle, dispatch, and monitor the incident?

- Did FEMS employees follow all rules,

policies, protocols, and procedures?

- Did first responders properly assess

the patient?

- Were FEMS written reports and oral

communication adequate?

- Did MPD responders properly assess

the situation at the scene, and were steps taken by MPD responders prior

to opening an investigation adequate?

- Did the second responders arrive

with all due and proper haste?

- Did the second responders properly

assess the patient?

- Did the second responders select an

appropriate hospital?

- Are there any identifiable

improvements to FEMS rules, policies, protocols, and procedures?

- Did Howard properly triage and

assess the patient upon his arrival at the hospital?

- Did the Office of the Chief Medical

Examiner promptly and completely discharge its review and report of the

death?

In addition to Mr. Bobb’s questions, the Office also

received inquiries from Councilmembers Phil Mendelson and Kathy

Patterson regarding issues of concern with respect to this matter.

Finally, the Rosenbaum family requested that the Office of the Inspector

General answer questions they posed “so that errors [they] experienced

are not repeated in the future ….”

We believe that this report is responsive to many of the

questions that have been raised.

The scope of the Inspector General’s review included

the entire emergency response provided to Mr. Rosenbaum on January 6,

2006, and the review conducted by the Office of the Chief Medical

Examiner.2

To conduct the review, the Inspector General appointed a

team of inspectors and investigators to examine the circumstances

surrounding the January 6, 2006 incident. The team members have training

and experience in law enforcement, firefighting, medical, and pre hospital

care.3 The team reviewed policies, procedures,

protocols, General and Special Orders, personnel files, patient care

standards, hospital and ambulance medical records, certification and

training records, and reports issued by FEMS, MPD, the Office of the

Chief Medical Examiner, and the Department of Health. The team also

interviewed all District government and Howard personnel involved in Mr.

Rosenbaum’s emergency care and autopsy. Upon conducting its review,

the OIG team noted multiple discrepancies in statements made by

interviewees. (See Appendix 1)

Office of Unified Communications

- The Office of Unified Communications

properly handled, dispatched, and monitored the Gramercy Street call.

The call taker and dispatchers who handled the 911 call carried out

their duties appropriately.

Recommendation

None.

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department

Engine 20

- Engine 20 personnel did not follow

all applicable rules, policies, protocols, and procedures. The

firefighter in charge of the Engine 20 crew on January 6 did not have a

current CPR certification as required. In addition, the

firefighter/Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) with the highest level of

pre-hospital training did not take charge of patient care during the

Gramercy Street call.

- Firefighter/EMTs did not properly

assess the patient. None of the firefighter/EMTs performed a complete

assessment of the patient, and not one of the patient’s vital signs4

was recorded at the scene. Once the firefighter/EMTs perceived an odor

of alcohol coming from the patient, they did not focus on other

possibilities as the cause of his altered mental status such as stroke,

drug interaction or overdose, seizure, diabetes, head trauma, or other

injury.

- Oral communication and standard

reports were not adequate. Firefighter/EMTs did not pass on key

information to the ambulance crew such as observing blood on the patient

and detecting the patient’s constricted pupils. Engine 20 personnel

did not prepare a written report on the Gramercy Street incident because

the FEMS form for such purpose is being revised.

Recommendations

- That FEMS ensure all personnel have current required

training and certifications prior to going on duty.

- That FEMS immediately implement a reporting form for

firefighter/EMTs who respond to medical calls so that first responder

actions and patient medical information can be documented.

- That FEMS develop and implement a standardized

performance evaluation system for all firefighters. The Office of the

Inspector General team determined that FEMS employees are not evaluated

on a regular basis, in the manner that other District government

employees are evaluated. Consequently, FEMS lacks standards to guide

firefighters’ performance and for use in evaluating their performance.

- That FEMS assign quality assurance responsibilities to

the employee with the most advanced training on each emergency medical

call. The designated employee should: (a) have in-depth knowledge of the

most current protocols, General Orders, Special Orders, and other

management and medical guidance; (b) monitor compliance with FEMS

protocols by all personnel at the scene; and (c) provide on-the-spot

guidance as required.

Metropolitan Police Department Responders

- MPD officers did not properly assess

the situation upon arrival. The three responding MPD officers did not

secure the scene, did not conduct an adequate preliminary investigation

in accordance with MPD General Orders, and did not take adequate steps

to determine if a crime had been committed. They also did not complete a

report on the incident pursuant to the relevant MPD General Order.

Recommendations

- That MPD immediately review and reissue the pertinent

General Orders relating to officer responsibilities at emergency

incidents. In addition, MPD should consider implementing or revising as

necessary a quality assurance program that includes supervisory review

of required reports, and a tracking system to ensure that reports are

written and retrievable for every call.

- That MPD assign quality assurance responsibilities to

the senior officer responding to each call.

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department

Ambulance 18

- EMTs did not follow applicable

rules, policies, and protocols. The highest-trained EMT, an EMT-Advanced,

was not in charge of the patient as required by protocol. The EMT-Advanced

did not assess the patient, or help her partner assess him. Neither EMT

adequately questioned the first responding firefighter/EMTs about the

patient’s vital signs, or other care and treatment. The patient’s

low Glasgow Coma Scale results were disregarded, and not brought to the

attention of Howard Emergency Department personnel.

- The ambulance did not arrive on the

scene expeditiously. The ambulance driver got lost after being

dispatched from Providence Hospital, and then did not take a direct

route to Gramercy Street. This error added 6 minutes to the trip. (See

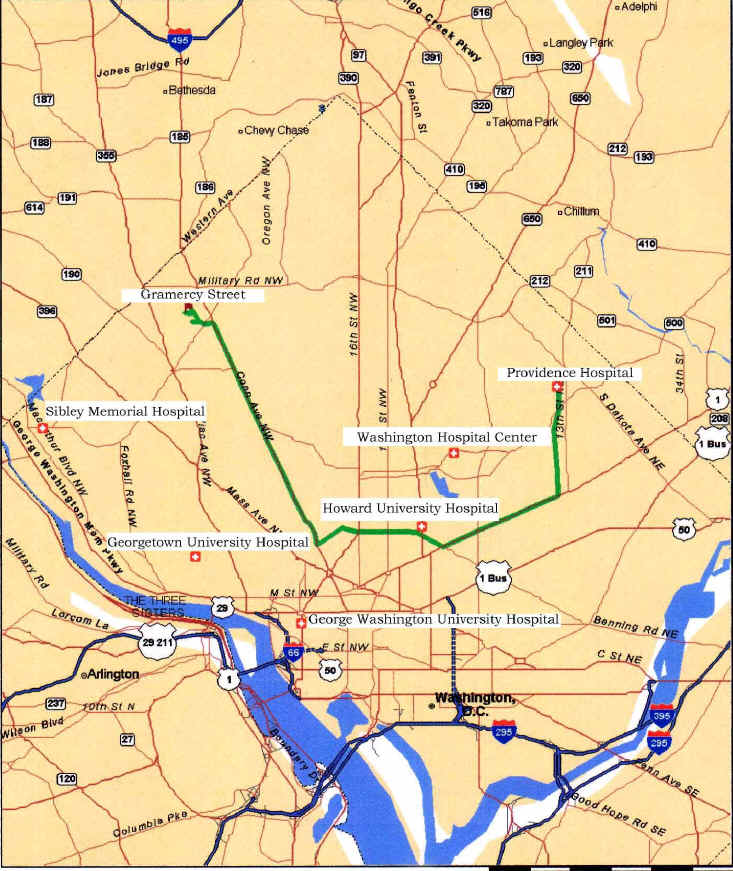

Appendix 2)

- EMTs did not thoroughly assess the

patient. The EMT who assessed the patient failed to conduct all of the

required assessments, and did not fully document his assessment and

treatment on the FEMS 151 Run Sheet. (See Appendix 3)

- Transport of the patient to the

hospital did not follow FEMS protocol. EMTs are required to transport

patients to the “closest appropriate open facility.” Although

Ambulance 18 was closest to Sibley Hospital, the EMT in charge, for

personal reasons, decided to transport the patient to Howard. Howard is

1.85 miles further from Gramercy Street than the Emergency Department at

Sibley Hospital. (See Appendix 4)

- EMTs did not properly document

actions. The EMT who cared for the patient did not completely fill out

the FEMS 151 Run Sheet. For example, the form shows no times when

treatment, care, or testing was provided or performed. An entire page of

the form relating to patient care was left blank.

Recommendations

- That FEMS ensure all personnel have current required

certifications prior to going on duty.

- That FEMS take steps to comply with its own policy on

evaluating EMTs on a quarterly basis.

- That FEMS promptly reassign, retrain, or remove poor

performers.

- That FEMS assign quality assurance responsibilities to

the most highlytrained pre-hospital provider for each incident. This

individual should: (a) have in-depth knowledge of the most current FEMS

protocols and other management guidance; (b) monitor compliance with

protocols and other guidance by all personnel at the scene; and (c) include

the results of on-scene compliance monitoring in all reports required by

management.

- That FEMS consider installing global positioning

devices in all ambulances to assist EMTs in expeditiously reaching their

destinations on emergency calls.

Howard University Hospital

- Nurses did not properly triage5 and

assess Mr. Rosenbaum. The triage nurse did not perform basic assessments

and did not communicate an abnormal temperature reading. The patient was

incorrectly diagnosed as intoxicated, but employees did not follow

triage policy on treating an intoxicated patient. Howard’s Patient

Care Standards—including monitoring airway and breathing, assessing

for trauma, conducting routine lab tests, and monitoring vital signs

every 15 minutes—were not followed.

Recommendations

- That Howard develop a system in the Emergency

Department that will allow staff to readily identify patients’

priority level while they are awaiting care.

- That Howard consider adopting a patient records system

that would enable nursing and medical staff to review documents when

they are at a patient’s side. The current system prevents staff access

to such information in a timely manner.

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner

- The Office of the Chief Medical

Examiner conducted the Rosenbaum autopsy expeditiously and promptly

issued a report.

Recommendation

- That Office of the Chief Medical Examiner consider using

digital camera technology to photograph all autopsies. The Office of the

Inspector General was unable to review requested autopsy pictures

because of photo processing delays and mislaid slides.

The OIG team concludes that personnel from the Office of

Unified Communications properly monitored the 911 call from Gramercy

Street and immediately dispatched adequate resources to respond to the

emergency. However, FEMS, MPD, and Howard personnel failed to respond to

David E. Rosenbaum in accordance with established protocols. Individuals

who played critical roles in providing these services failed to adhere

to applicable policies, procedures, and other guidance from their

respective employers. These failures included incomplete patient

assessments, poor communication between emergency responders, and

inadequate evaluation and documentation of the incident. The result,

significant and unnecessary delays in identifying and treating Mr.

Rosenbaum’s injuries, hindered recognition that a crime had been

committed.

On January 6, 2006, David E. Rosenbaum consumed alcohol,

both before and during dinner prior to leaving home for a walk.

Neighbors discovered Mr. Rosenbaum lying on the sidewalk in front of

their home and called 911. Upon assessment, emergency responders

concluded that Mr. Rosenbaum’s symptoms, which included poor motor

control, inability to speak or respond to questions, pinpoint pupils,

bleeding from the head, vomiting, and a dangerously low Glasgow Coma

Scale, were the result of intoxication. Hospital laboratory and other

tests, however, confirmed that Mr. Rosenbaum’s symptoms were caused by

a head injury. Emergency responders’ approach to Mr. Rosenbaum’s

perceived intoxication resulted in minimal intervention by both medical

and law enforcement personnel.

FEMS personnel made errors both in getting to the scene

and in transporting Mr. Rosenbaum to a hospital in a timely manner.

Ambulance 18 did not take a direct route from Providence Hospital to the

Gramercy Street incident. In addition, for personal reasons, the EMTs

did not take the patient to the nearest hospital. As a result of that

decision, it took twice as long for Ambulance 18 to reach Howard than it

would have taken to get to Sibley Hospital. Once FEMS personnel at the

Gramercy Street scene detected the odor of alcohol, they failed to

properly analyze and treat Mr. Rosenbaum’s symptoms according to

accepted pre-hospital care standards. Failure to follow protocols,

policies, and procedures affected care of the patient and the efficiency

with which the EMTs completed the call. In addition, FEMS employees’

failure to adequately and properly communicate information regarding the

patient affected subsequent caregivers’ abilities to carry out their

responsibilities.

MPD officers initially dispatched in response to the

Gramercy Street call failed to secure the scene, collect evidence,

interview all potential witnesses, canvass the neighborhood, conduct

other preliminary investigative activities, or properly document the

incident. Both FEMS and MPD failures were later compounded by similar

procedural failures on the part of Howard Emergency Department

personnel, who also initially believed Mr. Rosenbaum’s condition to be

the result of intoxication.

Upon Mr. Rosenbaum’s arrival at Howard, Emergency

Department personnel failed to properly assess his condition and failed

to communicate critical medical information to each other, thereby

delaying necessary medical intervention, all in violation of Howard’s

own patient care standards. Further, a number of Emergency Department

staff members passed Mr. Rosenbaum in the hallway and neglected to

provide clinical and therapeutic care.

The Office of the Inspector General’s review indicates

a need for increased oversight and enhanced internal controls by FEMS,

MPD, and Howard managers in the areas of training and certifications,

performance management, oral and written communication, and employee

knowledge of protocols, General Orders, and patient care standards.

Multiple failures during a single evening by District agency and Howard

employees to comply with applicable policies, procedures, and protocols

suggest an impaired work ethic that must be addressed before it becomes

pervasive. Apathy, indifference, and complacency—apparent even during

some of our interviews with care givers—undermined the effective,

efficient, and high quality delivery of emergency services expected from

those entrusted with providing care to those who are ill and injured.

Accordingly, while the scope of this review was limited,

these multiple failures have generated concerns and perceptions about

the systemic nature of problems related to the delivery of basic

emergency medical services citywide. Such failures mandate immediate

action by management to improve employee accountability. Specifically,

we believe that several quality assurance measures may assist in

reducing the risk of a recurrence of the many failures that occurred in

the emergency responses to Mr. Rosenbaum: systematic compliance testing,

comprehensive and timely performance evaluations, and meaningful

administrative action in cases of employee misconduct or incompetence.

The 911 call from Gramercy Street was received in the

Office of Unified Communications (Communications), which responds to

emergency and non-emergency calls in the District. Communications

centralizes the coordination and management of public safety

communication systems and resources. It is a consolidation of emergency

911, non-emergency 311, and 727-1000 calls for the MPD, FEMS, and

District government customer service operations.

Communications employs an automated system, I-Tracker,

that continuously tracks the location of all mobile emergency units and

identifies the closest unit that can be dispatched to an emergency event. It is Communications

policy to dispatch the closest appropriate unit to the scene of an

emergency.

Documentation provided by Communications management shows

that all universal call takers and dispatchers have the training

required for their positions. This includes training in basic anatomy,

systems of the body, management of different types of calls and callers,

and emergency medical dispatch procedures. Communications management

stated that the national standard for call takers and dispatchers does

not require them to be Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs).

Based on the answers elicited from a 911 caller,

predicated on a predetermined set of questions asked by the call taker,

an automated system6 categorizes and assigns a priority

designation7 to

each call. Dispatchers then use computer software to identify and

dispatch the closest available units. Radio operators give directions to

locations and provide other assistance as needed. The Director of

Communications stated that the system in place is one of the most widely

used and accepted by the emergency medical community.

According to the Fire and Emergency Medical Services

Department (FEMS) website, FEMS “provides fire protection and medical

attention to residents and visitors in the District of Columbia.” Fire

stations have engine companies and/or truck companies,8 and may have one

or more ambulances. Two paramedics9 are generally assigned to

Advanced Life Support (ALS) ambulances,10 although they

may be staffed by a paramedic and an EMT.11 Two EMTs are assigned to

Basic Life Support (BLS) ambulances. The District has 8 engine companies

with EMTs, 3 heavy-duty rescue squads with EMTs, 19 Paramedic ALS

ambulances, a Rapid Response, 24-hour ALS ambulance, and 17 BLS

ambulances.

When a call comes into a firehouse, a lighted sign alerts

the crew that they are being dispatched to an address, the reason for

the dispatch, and what other emergency responders are being dispatched

to the same call. BLS fire engines are stocked with oxygen, cervical

collars, and a “jump bag.” The jump bag contains plastic airways,

nonrebreather oxygen masks,12 nasal

cannulas,13 bandages, an obstetrical

kit, and vital signs testing equipment. There are no blankets,

stretchers, back boards, or medications on BLS fire engines. Upon

completion of any call, firefighters record minimal details such as

date, time, location, and nature of the call in a log book that is

maintained at the firehouse.

The FEMS Training Division in southwest Washington, D.C.

is responsible for training firefighters. Since 1989, all firefighters

have been required to obtain certification as EMTs. All recruits attend

the training academy for an 18-week course, 6 weeks of which are devoted

to EMT training. EMT candidates who are not firefighters are trained at

private EMT training institutions. In addition to formal training, all

EMT trainees must pass an EMT Basic Certification written and practical

skills examination. This one-day examination is administered by the D.C.

Department of Health, Office of Emergency Health Medical Services

Administration. A score of 75% is required to obtain certification as an

EMT. EMTs must obtain recertification every 2 years by attending a

40-hour refresher course and passing a practical and a written test. In

addition, all firefighters and EMTs must have CPR certification, which

is renewed after refresher training every 2 years.

The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration

(NHTSA), under the federal Department of Transportation, sets standards

and establishes guidelines and curricula for the nation’s emergency

medical services providers. According to NHTSA, there are three levels

of EMT certification: EMT-Basic, EMT-Intermediate, and EMTParamedic. In

2000, pursuant to Special Order 2005-17, FEMS instituted a protocol

course for “EMT-Advanced,” a local program that is intended to

“ensure the highest possibility of care.” The EMT-Advanced program

is not sanctioned by NHTSA. All EMTs were scheduled to attend the

additional protocol course, which included 2 weeks of didactic,

laboratory, and clinical training. Upon completion of all components of

the training, an EMT-Advanced could provide additional pre-hospital

services, such as administering certain medications and performing advanced

airway management. Nonfirefighter EMTs were trained first, and two

classes of firefighter/EMTs were trained in 2002. After 2002, however,

funding for continued training was no longer available, and EMT-Advanced

training ended. EMT-Advanced personnel are given a wallet card with the

EMT-Advanced designation. The card does not expire and EMT-Advanced

refresher training is not required.

FEMS protocols governing medical treatment are based on

NHTSA guidelines, state protocols, U.S. Department of Transportation

training curricula, EMT guidelines, and other reference materials.14 In

addition, FEMS publishes General Orders which dictate operational

procedures for all FEMS personnel. Special Orders update General Orders,

while Memoranda and Bulletins inform personnel of special issues or

changes of note. All FEMS personnel can access the General Orders,

Special Orders, and Memoranda online, and hard copies are kept in

binders at each firehouse. The current FEMS D.C. Adult Pre-Hospital

State Medical Protocols were approved in May 2002, partially revised in

2004, and “apply to every EMS agency that operates in the District of

Columbia.”

FEMS General Patient Care Protocols: EMT-Basic Scope of

Practice, at A-5.1 through A-5.2, outlines what certified EMTs are

authorized to do: evaluate the ill and injured; render basic life

support, rescue, and first aid; obtain diagnostic signs (e.g.,

temperature, blood pressure, pulse and respiration, level of

consciousness, and pupil status); perform CPR; use airway breathing

aids; use stretchers and body immobilization devices; provide initial

pre-hospital emergency trauma care; perform basic field triage; perform

blood glucose testing;15 initiate IV lines for

saline;16 administer

oxygen, glucose, and charcoal; administer selected medications;17 assist

EMT-Intermediates and EMTParamedics; manage patients within their scope

of practice; and transport patients.

The protocol for “Patient Care” states that after

assuring the EMT’s and the patient’s safety, and employing

precautions to prevent contact with body fluids, the EMT performs an

initial assessment “on every patient to form a general impression of

needs and priorities.” According to this patient care protocol, the

initial assessment includes an evaluation of:

- mental status18

- airway

- breathing

- circulation

- disability, which includes

performance of neurological assessment and injuries. This includes removal of clothing as necessary

and maintenance of spinal immobilization, if needed.

This section of the protocol includes a detailed chart

that addresses the “Appropriate Focused History and Physical

Examination” for the unresponsive and responsive patient, which

includes the detailed examination and ongoing assessment that is to be

performed. Upon completion of the assessment, the protocol requires that

a clinical priority be assigned as follows: Priority 1 is Unstable;

Priority 2 is Potentially Unstable; and Priority 3 is Stable.

A “Note Well”19 in the patient care protocol states:

“The provider with the highest level of pre-hospital training and

seniority will be in charge of patient care.”

The Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) is the primary

law enforcement agency for the District of Columbia. General Orders

establish policies and procedures for MPD officers.

MPD General Order SPT-401.01, entitled “Field Reporting

System,” dated March 4, 2004, states, in part, at page 3:

It shall be the responsibility of the first member on the

scene, regardless of his/her assignment, to begin conducting the

preliminary investigation after safety precautions have been taken and

the investigation does not interfere with the criminal case or defeat

the ends of justice.

The General Order “Procedural Guidelines” section

provides on pages 3-4:

The preliminary investigation is the combination of those

actions that should be carried out, as soon as possible, after the first

responding member arrives on the scene. At a minimum, he/she shall:

- Ensure that injured or sick persons receive medical

attention.

- Secure the crime scene to prevent the evidence from being

lost or contaminated.

- Determine whether a crime has been committed and, if

so, the exact nature of the offense or incident.

- Determine the identity of the suspect and make an apprehension when appropriate.

- Provide lookout information to the dispatcher and

other units, such as descriptions, method and direction of travel,

whether armed or unarmed, and any other identifiable information about

any suspect(s) and/or the suspect’s vehicle.

- Identify, interview, and take statements from all

victims, witnesses and suspects to determine in detail the exact

circumstances of the offense or incident.

- Arrange for the collection of evidence.

- Take any other action that may aid in resolving the

situation or solving the crime as directed by a supervisor.

The “Procedural Guidelines” section of this same

General Order further states that the preliminary investigation begins

when the first MPD Officer arrives on the scene of “a crime or

incident.” All information obtained is to be documented on appropriate

forms and submitted for review and signature. The section entitled

“Regulations” states that appropriate reports and paperwork are to

be completed for “[a]ny incident or crime that results in a member

being dispatched or assigned to calls for service.”

Howard University Hospital (Howard) is a 482-bed

university and teaching hospital. Its services include a Level I trauma

center and emergency department that responds to more that 48,000 visits

a year.

An Assistant Clinical Manager oversees all activities of

the Emergency Department, and a Charge Nurse supervises and directs the

patient care activities. One triage nurse is assigned to the ambulance

receiving area known as the “back triage,” and another triage nurse

is assigned to the “front triage” or “walk in” area, where all

patients seeking emergency care,20 are received. In addition, there also

is a “fast track” section for patients who need treatment for acute,

minor illnesses, such as earache, or minor lacerations not needing

sutures. Fast track care is available from 10 a.m. until 12 midnight.

The Emergency Department is organized into two teams:

“Red” and “Blue.” The Red Team works out of the rooms on

hallways “A” and “B,” and the Blue Team works out of the rooms

on hallways “C” and “D.” The teams function separately, with a

team leader and assigned staff nurses. Each team should be staffed with

three Registered Nurses and an “Emergency Department tech.” On

January 6, 2006, there were three registered nurses on the Red Team, two

on the Blue Team, and neither team had an assigned technician.

According to page 1 of the Howard Emergency Department

triage policy, “Triage is designed to provide timely assessment and

management of all patients” who arrive at the Emergency Department.

When a patient enters the Emergency Department, a triage nurse evaluates the patient, performs an assessment, and

indicates what level of care he or she needs. Levels of care are

described in the triage policy. For example, Level I patients have

“conditions which are critical and life-threatening, and which require

immediate therapeutic intervention ….” Level I conditions include

cardiac arrest, unconsciousness, or emergency child birth. According to

Howard’s policy, Level II patients have conditions which are critical

and require immediate intervention after triage. These conditions

include cardiac chest pain, sudden headache, and alcohol and drug

intoxication. Level III patients are defined as having conditions which

are not critical or life-threatening, but require immediate intervention

after triage and registration. Howard’s triage policy provides that

patients requiring Level III care, including those with abdominal pain

and victims of child abuse and sexual assault, should be seen within 2

hours. Level IV patients have conditions such as minor burns, dental

injuries, and allergic reactions, for which intervention can be delayed.

The Howard Policy for Admission, dated January 2005,

states that the triage nurse “will utilize the algorithms21 in

determining the priority level of care appropriate to manage the

patient.” According to the algorithm for alcohol abuse, found in the

Howard Emergency Department Triage Manual, a patient with any of the

following is considered a Level II patient:

- abnormal vital signs

- altered mental state (including

combative, loud, inappropriate behavior)

- non-ambulatory

- history of fall or syncope22

- history of acute seizure episode.

A patient with these symptoms goes to the main Emergency

Department, where the staff is to “urgently proceed.” If none of the

above signs are present, the patient is a Level IV.

According to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner

home page on the D.C. government website, the Chief Medical Examiner:

Investigates and certifies all deaths in the District of

Columbia that occur as the result of violence (injury) as well as those

that occur unexpectedly, without medical attention, in custody, or pose

a threat to public health.

At approximately 9:20 p.m. on January 6, 2006, a resident

of Gramercy Street, N.W. (Neighbor 1) observed an unknown man lying on

the sidewalk directly in front of his house. According to Neighbor 1, he

approached the man, who was lying face up on the ground, and saw that he

appeared to be ill or injured. He was unable to rise. When Neighbor 1

spoke to the man, he responded with groans. Neighbor 1 called to his

wife, Neighbor 2, and told her to dial 911 for assistance. Neighbor 2

relayed the 911 call taker’s questions about the man to her husband.

She then relayed her husband’s answers to the 911 call taker. After

ending the call, Neighbor 2 went outside to see if she could help the

man. According to Neighbor 2, the man was “dressed nicely and not

unkempt.” Stereo headphones were lying next to him, and as he kept

raising his left arm, she noticed that he was wearing a watch and a

wedding band.

Neighbor 2 stated that the man’s eyes did not connect

with hers when she spoke to him, and he did not appear to understand

what was being said to him. He was using only the left side of his body,

as he kept trying to sit up. However, he would fall back each time,

striking his head on the ground. He appeared unable to use his right

side, and was never able to sit up or stand up. Neighbor 2 also stated

that her husband, who was wearing slippers, placed his foot under the

man’s head to keep it from hitting the ground. Neighbor 2 brought a

blanket from the house and covered the man, and she and her husband

knelt on either side of him while waiting for the ambulance. Neighbor 1

stated that he did not notice any bleeding, physical harm, or trauma to

the patient’s body from the time he found him until he was transported

to the hospital. However, after the man was put into the ambulance,

Neighbor 1 did notice a wet spot on the ground where the man had been

lying. He stated that he could not tell what it was until the next

morning, when he recognized it as blood.

According to Communications records and recordings, the

911 call from Neighbor 2 was answered by a call taker at 9:27 p.m. The

call taker interviewed Neighbor 2 by using software-generated questions

to assess the nature of the problem. According to the call taker, after

she keyed in the answers provided by Neighbor 2, the software made an

assessment of the call and produced a description of “Unknown Problem

(man down).” The software also determined that a dual response by FEMS

and MPD was warranted. This information was transmitted electronically

to both the FEMS and MPD dispatchers.

In July 2005, FEMS issued a policy change entitled

“Revised Dispatch Policy Change # 3.” The purpose of the policy

change was “to improve ALS and BLS response times by dispatching ALS

units on Charlie and Delta Level responses and BLS units on Alpha and

Bravo Level responses.” According to this policy, “Bravo Level calls

will be handled by a first responder and a Basic Life Support Unit. ALS

units will no longer be dispatched on Alpha or Bravo Level calls.” The

policy further states that if the first responders (firefighter/EMTs) on

the scene request an ALS unit, they must notify Communications with an

update on the patient’s condition, and the requested ALS unit will be

dispatched. The Gramercy Street call was classified as requiring a

“Bravo” level (BLS) response from FEMS.

Using the information elicited by the call taker, the

software identified, selected, and recommended as first responders,

Engine 20, and BLS Ambulance 18. The Communications Event Chronology23

indicated that Engine 20 was .54 miles, and Ambulance 18 was 5.61 miles

from the Gramercy Street incident. At 9:30 p.m., the FEMS dispatcher

radioed Engine 20, located at 1617 U Street N.W., and Ambulance 18,

which was at Providence Hospital (Providence) on Varnum Street, N.E., to

respond to the Gramercy Street incident.

According to the Event Chronology, at 9:31 p.m., MPD unit

2022 was dispatched to respond to the Gramercy Street call.

Communications software had designated the call a Priority 2, and

required the dispatcher to relay this information to a police unit

within 10 minutes. At 9:37 p.m., MPD unit 2021 with Officer 1 and

Officer 2, contacted Communications and advised that they would take the

Gramercy Street call, and that MPD unit 2022 should disregard that call.

MPD unit 2022 driven by Officer 3 acknowledged this message, but advised that she would

respond to the location and would “remain in service.”

Communications staff followed

protocols. Based on the Office of the Inspector General’s (OIG) review

of Office of Unified Communications’ protocols, procedures, tape

recordings, and employee interviews, the OIG team determined that the

call taker and dispatchers who handled the Gramercy Street 911 call

carried out their duties appropriately. According to Neighbor 2, when

she made the 911 call, the call taker was thorough, helpful, and

courteous. Further, the team’s review of the taped 911 call shows that

the call taker worked according to the predetermined script, and sent

the call information to the FEMS and MPD dispatchers within the allotted

time of 60 seconds.

None.

On January 6, 2006, at 9:30 p.m., Communications

dispatched Battalion 4, Engine 20, headquartered at 1617 U Street, N.W.,

to the Gramercy Street 911 call. According to interviews and the Event

Chronology, Engine 20, a BLS vehicle, arrived on the scene at 9:35 p.m.

Four firefighters responded to the Gramercy Street 911

call: FF, FF/EMT 1, FF/EMT 2, and FF/EMT 3. A review of FEMS personnel

records showed that three of the four, FF/EMT 1, FF/EMT 2, and FF/EMT 3

had current EMT certifications.24 FF/EMT 2 was an EMT-Advanced. FF, who

was the officer in charge that evening, had never been trained or

certified as an EMT.

FF has been a firefighter at Engine Company 20 for 24

years. When he was hired, EMT training was not required. After such

training became a requirement, FF still never received training.

According to FF, he “just fell through the cracks.” FF informed his

supervisor about his lack of training but was never put into a class.

The last time FF tried to get into a class was 6 years ago. FF’s CPR

certification expired 2 years ago, and he does not have first aid

training.

On January 6, FF’s immediate supervisor was sick, and

he was designated as the “acting officer in charge,” supervising the

activities of the crew assigned to Engine Company 20. FF was assigned to

this supervisory position even though he was not trained, certified, or

in any way qualified to oversee the firefighter/EMTs’ care and

treatment of ill or injured persons.

According to FF, Engine Company 20 personnel received a

call for a “man down” on Gramercy Street, N.W. around 8:30 or 9 p.m.25 They responded and found a man lying on the sidewalk. The

firefighter/EMTs began attending to the patient. The patient immediately

began to vomit, and the firefighter/EMTs had to clean him up with gauze

pads retrieved from the jump bag. The vomit smelled like alcohol. “It

was like food, not a lot of vomit. It kind of dribbled down his

jacket.” When asked who put gauze to the back of the patient’s head,26 FF initially stated, “[FF/EMT 2] or [FF/EMT 1].” Later in

the interview, FF stated, “I don’t remember anyone placing gauze on

the patient’s head. We used gauze to clean up the vomit.”

FF radioed dispatch to ask for status of the responding

ambulance and was told that Ambulance 18 was responding from Providence.

He could tell by the radio traffic that it was pretty busy that night

and that only a few ambulances were available.

FF spoke with the couple who had called 911. Neighbor 1

said he was going out to his car when he saw the patient. FF/EMT 1

started a patient assessment to check for injuries, and Neighbors 1 and

2 placed a blanket on the patient. FF/EMT 1 was holding the patient in

the sitting position with FF/EMT 1’s legs supporting the patient’s

back.

FF/EMT 3 took the first set of vital signs, and FF/EMT 2

the second. FF “watched them do this because [he] wanted to make sure

[his] guys were doing the right things.” The firefighter/EMTs wore

gloves, and he saw them “feel for trauma and blood. They found no

signs of trauma or blood.” The patient vomited at least two more

times. FF stated that the patient “never spoke, but was conscious and

a little combative when we tried to place oxygen on him.”

The lighting in the area where the firefighter/EMTs were

working was dim. FF’s recollection was that he turned the truck light

on to provide more illumination. FF stated that a female police officer

arrived and stayed in the car. Soon after, other MPD officers arrived.

After Engine 20 firefighter/EMTs had “taken the

patient’s vitals and stabilized him, all the ambulance had to do was

pull the stretcher out and take the patient to the hospital.” When the

ambulance arrived, FF talked with a female EMT, who asked, “What do we

have?” One of the firefighters replied by telling her, “ETOH.”27

The male EMT never inquired about the patient. Either FF/EMT

2 or FF/EMT 3 gave the female EMT the patient’s vital signs, which had

been written on a firefighter/EMT’s glove. FF did not see her write

them down. The male EMT placed the patient into the back of the

ambulance, and the female EMT sat in the driver’s seat. FF asked where

they were going and the female EMT stated, “Howard.”

When asked about the firefighters’ EMT training and the

level of pre-hospital care they could provide, FF stated that no one was

an EMT-Advanced.28 He knew this because their nametags would show their

status.

Subsequent to the Gramercy Street call, FF wrote a report

as directed by FEMS officials, and submitted it to his battalion chief.

On January 18, an interview panel comprised of FEMS and Department of

Health officials at Company 20 firehouse interviewed him about the

Gramercy Street call.

FF/EMT 1 has been a firefighter/EMT since May 1992. He

was recertified as an EMT-Basic in the fall of 2004. FF/EMT 1 is based

with Engine Company 9, but on January 6, he was detailed to Engine

Company 20 to help staff a shift that was shorthanded. FF/EMT 1 stated

that Engine 20’s regular driver, FF, was the acting officer in charge

that night.

FF/EMT 1 recalled that when Engine 20 arrived at the

Gramercy Street address, “two or three, but not more than four, people

were standing right over” a man lying on the sidewalk. The man was on

his back, moving and moaning. He described the man’s movement as

“squirming,” and remembered that the patient must have vomited

because he saw vomit on him. FF/EMT 1 stated that he did not smell

alcohol at that time.

According to FF/EMT 1, he helped FF/EMT 2 and FF/EMT 3

take the patient’s left arm out of his jacket so that someone could

take his blood pressure. They sat the patient up and took turns holding

him in a sitting position because he was vomiting. FF/EMT 1 recalled

that the patient vomited at least twice while Engine 20 was there. FF/EMT

1 stated that he checked for a medical identification (ID) bracelet, but

he did not find one. He stated that he usually performs this kind of

check, “especially when people can’t talk.” FF/EMT 1 remembered

hearing one of his colleagues announce that he was going through the

patient’s pockets looking for identification, but could not remember

who said it. FF/EMT 1 explained that firefighter/EMTs say this out loud

to avoid the perception by observers that they are searching patients’

pockets in order to steal their belongings.

FF/EMT 1 put an oxygen mask to the patient’s face and

“cranked it up,” meaning that he was giving the patient 15 liters of

oxygen per minute in order to “get him to come around.” When asked

if the patient was unconscious, FF/EMT 1 responded, “He was moaning,

and he couldn’t respond. I didn’t know what was wrong.” The

patient repeatedly took the oxygen mask off, and FF/EMT 1 kept putting

it back on. FF/EMT 1 stated that he did not know who took over the

oxygen mask duty when he left the patient’s side, but there were three

firefighter/EMTs and, “We were all doing everything. We all switched

up.” He stated that he could not describe what the other firefighter/EMTs

did for the patient because he was concentrating on giving the patient

the oxygen, which “was hard enough.” FF/EMT 1 could not say whether

other firefighter/EMTs gave the patient medications, performed an

assessment, provided any other care, or determined the cause of the

patient’s illness.

When FF/EMT 1 was asked what firefighter/EMTs are

required to do when they arrive at an emergency, he stated, “all we

are supposed to do is take vital signs and stabilize until transport

comes.” When asked what stabilizing efforts might be made for a “man

down,” FF/EMT 1 replied, “There’s a long list of stuff we could

do. I don’t know.” He then said that firefighter/EMTs could do

“everything except push drugs.” FF/EMT 1 also stated that

firefighter/EMTs could radio to Communications and inform the call

center that a call is of a more or less serious nature than originally

dispatched. FF/EMT 1 did not describe any medical urgency related to the

patient’s condition. In addition, since the man had no medical alert

bracelet identifying him as a diabetic, the firefighter/EMTs did not

consider him to be a diabetic.

FF/EMT 1 went to the truck and turned on the sidelights.

The position of the truck and its lights did not make the illumination

“real bright,” but it was better than without them. FF/EMT 1

returned to the patient and continued giving oxygen. At some point, two

MPD officers arrived, but FF/EMT 1 did not know them, nor was he able to

describe what they said or did. FF/EMT 1 remembered that

the night was cold, and he heard other firefighters ask for a blanket,

which a citizen provided. The firefighter/EMTs used the blanket to cover

the patient. The patient was shaking his head and vomiting, which made

the vomit “go everywhere.” FF/EMT 1 could smell alcohol, but he

thinks it was the vomit.

After the ambulance arrived, the ambulance crew did not

ask FF/EMT 1 any questions, and he did not talk to them. He overheard

others talking to them, but was not paying attention to what was being

said. FF/EMT 1 helped one of the ambulance EMTs put the patient on the

ambulance cot and move the patient into the ambulance.

Engine 20 returned to the firehouse, and FF/EMT 1

completed his shift at 7 a.m. on January 7. FF/EMT 1 did not make a

written report on January 6 on the care provided to the patient but

noted that “generally,” the firefighter/EMT who assesses the patient

writes notes and vital signs “on the glove or whatever” and gives

the glove to the ambulance personnel.

When FF/EMT 1 returned to work on January 10, there was

an order that he write a special report regarding the Gramercy Street

call. FF/EMT 1 wrote the report, and submitted it to his battalion

chief. He stated that an interview panel at Company 20 firehouse

interviewed him about the Gramercy Street call.

FF/EMT 2 has been a firefighter/EMT with FEMS for almost

4 years and has been at Engine Company 20 for the last 1½ years. Both

his CPR and EMT certifications are current. FF/EMT 2 has received EMT-Advanced

training.

FF/EMT 2 recalled that on January 6 the regular engine

driver, FF, was the acting officer in charge. FF/EMT 2 was the engine

driver for the night. When Engine Company 20 personnel arrived at the

Gramercy Street address, they saw a person lying on the sidewalk.

According to FF/EMT 2, the driver usually does not leave the truck.

However, he could see that the patient was vomiting, and because he had

the highest level of training, he left the truck to assist his

colleagues.

One of the firefighter/EMTs performed a sternum rub29

when they first arrived, and FF/EMT 2 gave the patient oxygen via a non-rebreather

mask. However, the patient vomited again. FF/EMT 2 removed the oxygen

mask so the patient could vomit freely. After FF/EMT 2 removed the

oxygen mask, he smelled alcohol. FF/EMT 2 recalled that when FF/EMT 1

put the oxygen mask back on the patient’s face, the patient “kind of

grimaced and pushed the oxygen mask away from his face.” FF/EMT 2

described the patient as “in and out of it,” but the oxygen

“brought him around. The patient was compliant, but didn’t like the

oxygen. If I tapped him he would look around at me.”

When MPD officers arrived on the scene, FF/EMT 2 asked

them if he could check the patient for identification. FF/EMT 2 went

through the patient’s pockets, but did not find anything.

FF/EMT 2 stated that he performed a patient assessment,

took the patient’s vital signs, and checked the patient’s head. His

assessment consisted of palpating30 the patient’s head, upper back,

neck, lower back, and the front of his chest. He found a speck of blood

on the patient’s head above his right ear. There was no swelling, and

there were no lacerations. FF/EMT 2 applied pressure to the patient’s

head with 4 x 4 gauze pads. This stopped the bleeding, which was

minimal. FF/EMT 2 “checked [the patient’s] motor responses and they

were fine.” FF/EMT 2 wrote the patient’s vital signs on a piece of

paper, which he retrieved from the jump bag, and gave the paper to FF/EMT

3. When he was asked if he always writes the vital signs down, FF/EMT 2

replied, “Yes, this is how it’s done.” Vital signs are recorded

and the writing is provided to the ambulance crew. FF/EMT 3 also took

vital signs as well as at least two additional blood pressure readings.

FF/EMT 2 recorded FF/EMT 3’s readings.

According to FF/EMT 2, FF/EMT 1 performed an assessment

of the patient’s lower body, which included everything below the

patient’s waist. The patient was sitting up with help from FF/EMT 1,

who had the patient’s back against his legs to hold him up. FF/EMT 2

stated that the patient would look at the firefighters but would not

respond when asked a question. FF/EMT 2 stated that the patient wore a

wedding band and a “nice” watch, and there was a one-piece radio

headphone set in the grass nearby.

According to FF/EMT 2, “It was cold that night, so I

got a blanket from the truck and a person that was standing there, a

female neighbor, placed a nice blanket on the patient. I remember

hearing someone say, ‘Get the blanket; get the blanket,’ because the

patient was vomiting [on it].” The firefighter/EMTs placed the patient

on the neighbor’s blanket to get him off the ground, and placed the

firefighters’ blanket on top of him.

When asked if he checked the patient’s pupils, FF/EMT 2

replied, “Yes, with my Streamlight.”31 According to FF/EMT 2, the

pupils were constricted, meaning small and not reacting to light.

Because the interviewers recognized this as a symptom requiring further

assessment, they asked if he was sure of the pupil response. FF/EMT 2

then changed his statement and said the patient’s pupils did react,

and they “contracted,” meaning they became smaller when exposed to

light.

The ambulance arrived, and the female EMT asked the

firefighters, “What we got?” FF/EMT 3 told her, “ETOH.” FF/EMT 1

and FF/EMT 3 helped the Ambulance 18 crew load the stretcher with the

patient onto the ambulance, and care of the patient was transferred to

the EMTs. The patient was not placed on a back board and did not have a

neck collar. Engine 20 returned to the firehouse after clearing trash

from the scene.

FF/EMT 2 wrote a report and submitted it to his battalion

chief. FF/EMT 2 stated that an interview panel at Engine Company 20

firehouse interviewed him about the Gramercy Street incident.

FF/EMT 3 has been a FEMS firefighter for 15 years. He has

worked at Engine Company 20 for 4 years. FF/EMT 3 remembered they

received a call at the firehouse on January 6 to Gramercy Street for a

“man down.” Engine 20 arrived on the scene and FF/EMT 3 went to the

side of the truck to retrieve supplies. The other firefighters went to

the patient. While he was retrieving supplies, a woman approached and

told him she had found the man on the ground.

The patient was vomiting by the time FF/EMT 3 got to him.

FF/EMT 3 repositioned the patient’s head so he would not choke. The

vomit looked like a full meal and was red. FF/EMT 3 then assessed the

patient’s level of consciousness. He stated that the patient:

was looking at me sarcastically. He never said anything.

I could smell the alcohol reeking from him, like it was coming out of

his pores. I tried talking with him, but he didn’t speak. I told him

we were going to take his blood pressure, but he was not really

complying.

FF/EMT 3 took one of the man’s arms out of his coat in

order to take his blood pressure.

Because the patient did not tell them what was wrong,

they performed a head-totoe assessment. After checking the patient, FF/EMT

3 saw a speck of what he thought was blood on his white gloves. He

checked the patient again but could not find where the speck came from.

He stated he thought it was food from the vomit.

Firefighter/EMTs tried to give the patient oxygen at 25

liters per minute, but the patient took the oxygen mask off. FF/EMT 3

stated that the patient “kept rolling his eyes at me.” FF/EMT 3

stated that the patient was not combative and was “okay after I turned

down the oxygen. He let the oxygen mask stay on a lot longer.” The

only thing notable about the patient’s condition was that he did not

respond verbally or follow commands.

FF/EMT 3 stated that when MPD units arrived, there were

two black male officers and “one black lady [officer] in her vehicle,

chillin’.” FF/EMT 3 told one officer standing nearby that he was

going to go through the man’s pockets for ID but could not find any.

FF/EMT 3 stated, “Just from growing up, I thought something was wrong.

I found it odd that the patient did not have a wallet or ID on him. No

one usually walks around with nothing. I told the guys, ‘Somebody got

him,’ meaning he was robbed.” His colleagues said, “Yeah,

something’s wrong.” The MPD officer just shrugged.

FF/EMT 3 stated that he took one set of vital signs,

which he explained included “pulse, respiration, and blood

pressure.” FF/EMT 2 took vital signs two more times.

FF/EMT 3 stated that he “took the lead, but mostly I

had [FF/EMT 2] doing most of the stuff. Even though [FF/EMT 2] is a

higher level by training, because he’s an EMTAdvanced, I always take

the lead because I have more time on [the job].” The patient’s vital

signs were stable, and FF/EMT 2 wrote them on the back of his glove. FF/EMT

3 stated, “I never write down vitals. How hard is it to remember them?

I give it to them [the ambulance crew] orally.” FF/EMT 2 told him that

the patient’s pupils were “pinpoint,”32 meaning, according to FF/EMT

3, “small.” According to FF/EMT 3, FF/EMT 2 did not give him

anything in writing.

The ambulance arrived, and FF talked to the female EMT. A

male EMT put the patient into the back of the ambulance. FF/EMT 3 gave

an oral briefing to the male EMT on the patient’s vital signs.

FF/EMT 3 wrote a report and submitted it to his battalion

chief. An interview panel at Engine Company 20 firehouse interviewed him

about the Gramercy Street incident.

Neighbors 1 and 2 told the OIG team that while the

arrival time of the fire truck was good, they believed the ambulance

took too long to get there. When the firefighter/EMTs arrived, Neighbor

2 asked them if they would be able to help and “kept trying to talk to

them,” but they did not pay any attention to her. Neighbor 2 thought

the injured man had a stroke. She believes that she heard the

firefighters rule out a stroke or heart attack. Neighbor 1 heard the

firefighters say that “9 out of 10 times it’s alcoholrelated.”

Neighbors 1 and 2 did not smell alcohol on the patient’s breath.

Neighbor 2 saw the firefighter/EMTs give the patient

oxygen, and that seemed to make him vomit. She saw him vomit twice. The

firefighter/EMTs wiped the vomit from his mouth with what looked like a

“Kleenex.” They kept trying to sit him up, and at the same time,

they were “tapping on his chest.” According to Neighbor 2, the

firefighter/EMTs did not appear to know what they were doing. She

explained that they were not cohesive and were just standing around not

doing anything specific other than giving the patient oxygen and waiting

for the ambulance.

- Firefighter had no CPR

certification. FEMS protocol requires that all fire personnel have

current CPR certification. FF advised that his CPR certification has not

been current for 2 years. Despite his expired CPR certification and the fact that he was not an EMT, FF was

in charge of the crew. He also stated that he monitored their actions to

ensure that they performed correctly.

- EMT with highest level of

pre-hospital training not in charge. The firefighter/EMT with the

highest level of pre-hospital training, FF/EMT 2, did not take charge of

patient care during the Gramercy Street call as required by protocol.

- Oxygen delivery contrary to

protocol. FF/EMT 3 administered oxygen to the patient at 25 liters per

minute (LPM). This action exceeded both FEMS protocol33 and accepted

medical practice of 15 LPM.

- Perceived alcohol intoxication

dictated firefighter/EMT actions. Firefighter/EMTs could not obtain a

health history or a cogent response from the patient. They stated that

they smelled alcohol, and assumed that the patient’s altered mental

status was solely caused by intoxication. Firefighter/EMTs did not

consider that in addition to having consumed alcohol, the patient could

be experiencing other illnesses or conditions such as stroke, drug

interaction or overdose, seizure, or diabetes. They also disregarded the

possibility that head trauma or other injury could have contributed to

his altered mental status.

- Spinal cord injury potential

disregarded. FF/EMT 1 described sitting the patient up and removing his

clothing prior to assessing him for head, spinal, or other injuries

which would have made moving the patient from a prone position

inadvisable. FF/EMT 3 described moving the patient’s head prior to

assessing his level of consciousness or the presence and extent of

injury. In addition, firefighter/EMTs described their continuing efforts

to keep the patient in an upright position, despite the patient’s

inability to sit up, which is an indication of possible head or spinal

cord injury.

- Diabetes discounted due to absence

of medical ID bracelet. Firefighter/EMTs made assumptions about the

patient’s medical condition because of the absence of a medical ID

bracelet. FF/EMT 1 stated that the absence of a medical ID bracelet for

diabetes eliminated their concern that diabetes was the cause of the

Gramercy Street patient’s current condition.

- No patient priority assigned.

Firefighter/EMTs did not perform a neurological assessment of the

patient, and did not assign the patient a priority as required by the FEMS Patient Care Protocol. This

protocol is described in the “Operations and Protocol” section of

this report.

- Faulty patient assessment. No single

firefighter/EMT performed a complete patient assessment, which resulted

in a patient assessment that was disjointed and incomplete. According to

the firefighter/EMTs, they divided the patient’s body in half. One

assessed the lower body, while the other assesed the top half. Two took

the patient’s blood pressure a total of four times, two took vital

signs, two gave oxygen, and one checked the patient’s pupils. None of

the vital signs was recorded, and only one set was communicated verbally

to the male EMT.

- Suspicion of criminal attack not

followed-up. When firefighter/EMTs checked for the patient’s ID, they

noted that he did not have a wallet or any ID on his person. FF/EMT 3

relayed to the OIG team that he said out loud, in the presence of his

colleagues and an MPD officer, that he thought the patient had been

robbed. However, even though his FEMS colleagues agreed that something

was “wrong,” neither FF/EMT 3 nor the other firefighter/EMTs

conducted a thorough assessment of the patient for assault-related

injuries or communicated this concern to the EMT who assumed care of the

patient. FF/EMT 3 also did not connect his stated suspicion to the

physical signs he observed. These indicators included vomiting,

combativeness, bleeding, and non-responsiveness, all of which are

symptoms indicative of a head injury.34

- Inadequate assessment performed

after blood found. Firefighters/EMTs FF/EMT 2 and FF/EMT 3 described

finding blood when they examined the patient. Neither reported using the

available flashlight to inspect the patient’s head and body for the

source of the blood.

- No follow-up to critical finding

regarding pupils. FF/EMT 2 told FF/EMT 3 that the patient’s pupils

were “pinpoint,” meaning that the pupils were constricted and

unresponsive. FF/EMT 3 stated that he, FF/EMT 3, had seniority and

always “took the lead.” Both firefighter/EMTs should have known that

pinpoint pupils are abnormal and warrant follow-up. However, neither

conducted any follow-up, nor did they connect the condition to other

symptoms the patient displayed. In addition, neither FF/EMT 2 nor FF/EMT

3 conveyed this information to Ambulance 18 EMTs.

- Scope of EMT practice misunderstood.

FF/EMT 1 gave an incomplete description of firefighter/EMTs’

responsibilities as “taking vitals and stabilizing the patient until

transport arrives.” In addition, FF/EMT 1 incorrectly described the

scope of EMT practice as “EMTs can do everything except push drugs.”

FEMS protocols clearly describe the EMT scope of practice, which is summarized in the “Operations and

Protocols” section of this report.

- Oral communication flawed.

Firefighter/EMTs at the scene conveyed minimal information to the

Ambulance 18 EMTs upon their arrival. Although FF/EMT 2 and FF/EMT 3

noted seeing blood when they examined the patient, they did not relay

this information to Ambulance 18 EMTs. FF/EMT 2 told FF/EMT 3 that the

patient’s pupils were constricted; however, neither FF/EMT 2 nor FF/EMT

3 relayed this information to the EMTs. FF/EMT 3 stated that he thought

the patient had been robbed, but did not convey his suspicion to

Ambulance 18 EMTs. According to the firefighter/EMT statements, vital

signs were assessed multiple times; yet the male EMT stated that he only

received one set of vital signs verbally from FF/EMT 3. FF/EMT 3 told

the male EMT that the patient was “just intoxicated.”

- FEMS requirement for written report

not followed. There was no written patient care report prepared on

January 6 by any firefighter or firefighter/EMT who responded to the

Gramercy Street incident. However, FEMS Special Order Number 49, “Fire

Fighting Division Units on Medical Locals,” dated September 6, 1996,